Are You Ready, Willing, and Able?

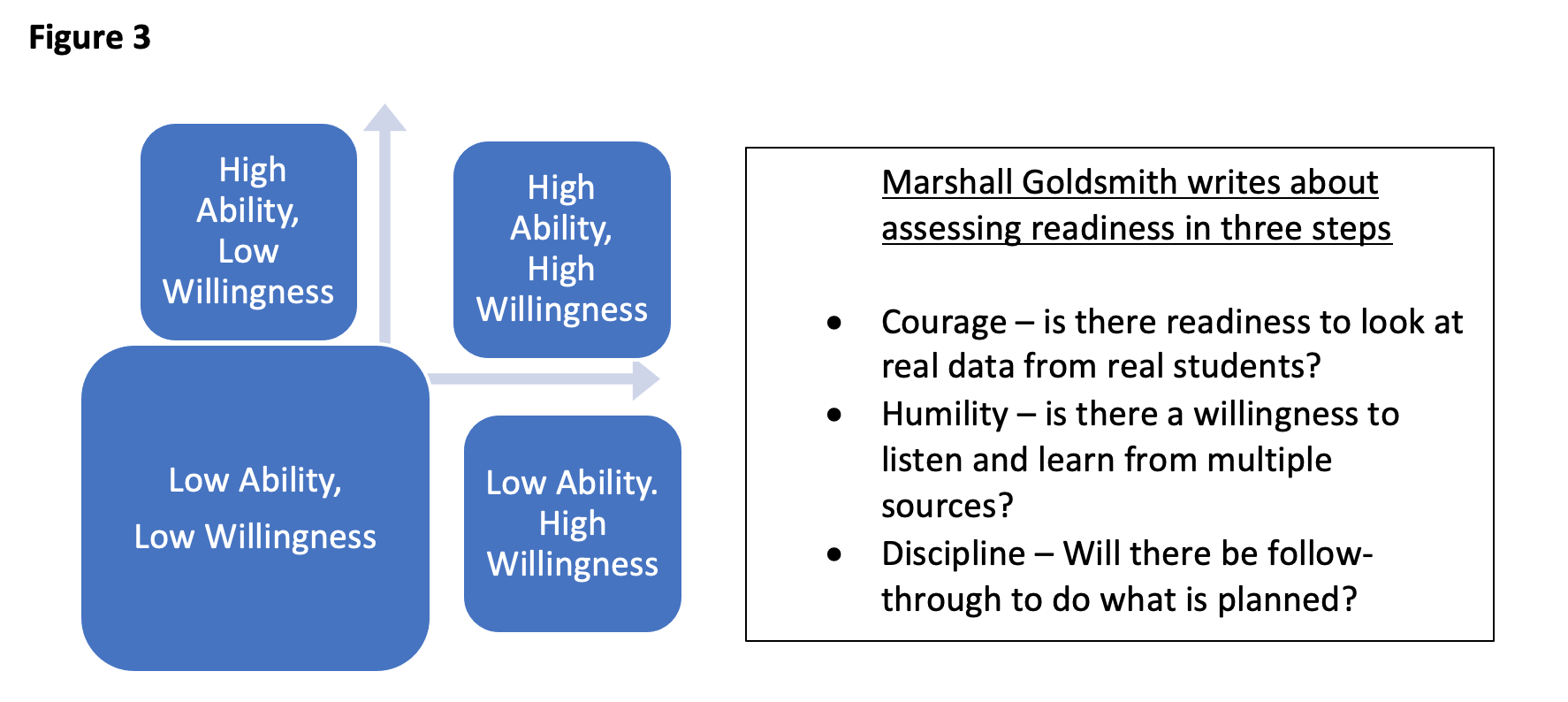

This rule is inspired by a friend and colleague, Frank Wagner, Marshall Goldsmith Stakeholder Centered Coaching expert and former professor at UCLA. When Frank was teaching his last summer class at UCLA, I attended his workshop on Situational Leadership, a model developed by Paul Hersey. I have edited this model for simplicity

Hersey’s work basically looked at groups in terms of readiness. And, based on the readiness, what leadership styles were best suited to work with the group. I have used this in the past in my leadership and coaching to assess individuals and groups. If you are in a leadership role, whether it be formal or informal, this may help to facilitate learning and increase effectiveness.

Why is this important? Here is Peter Senge’s quote: “The only sustainable source of competitive advantage is your organization’s ability to learn faster than your competition.” I think about this in terms accelerating adult learning.

- What increases learning for adults and students in your school or organization?

- How can I, as a leader, contribute to creating a culture which increases learning?

- And, personally, how can I accelerate my own learning?

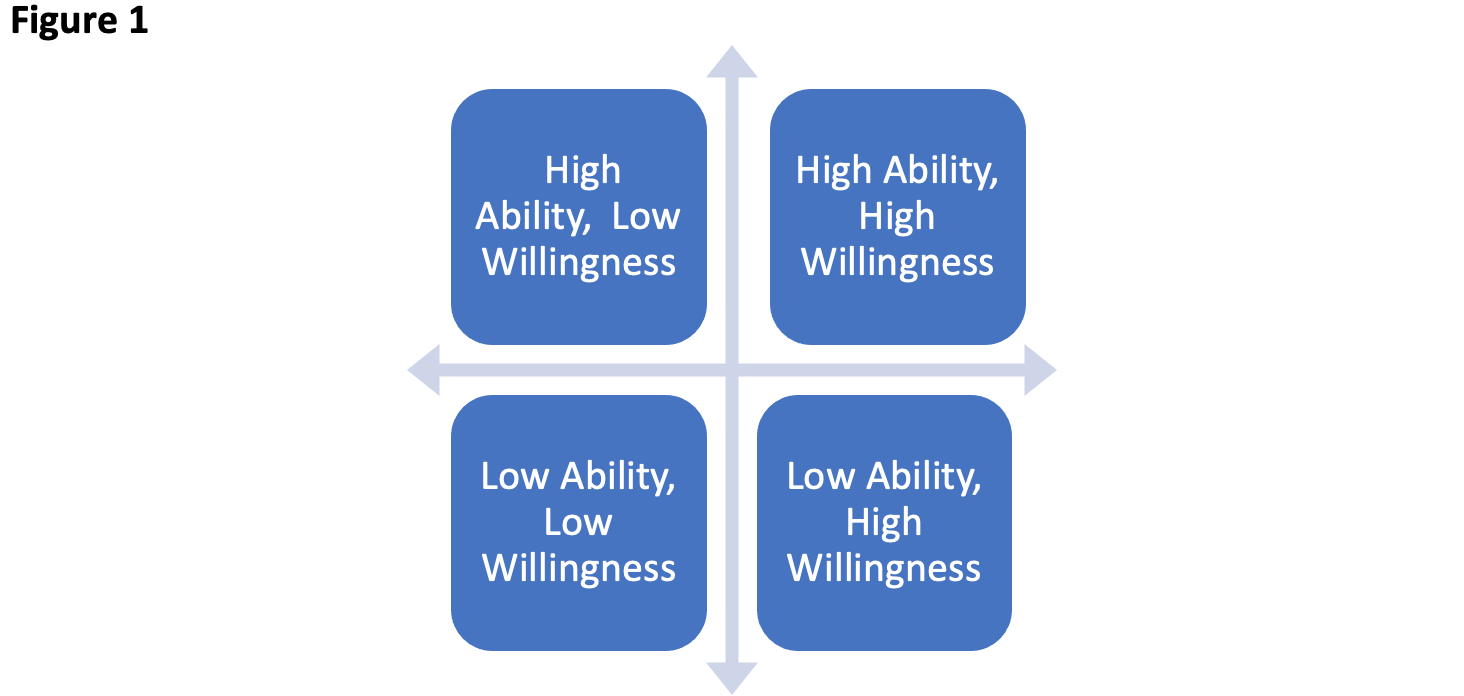

So, are you, and others ready, willing, and able. This readiness graphic looks at two axes. The ‘x’ axis is about willingness. Does the person or group demonstrate a willingness to learn? Do they do what they say? What do their actions indicate? The ‘y’ axis is the current ability level. Does the individual or group have the skill level and the repertoire necessary to increase the learning of themselves and others.

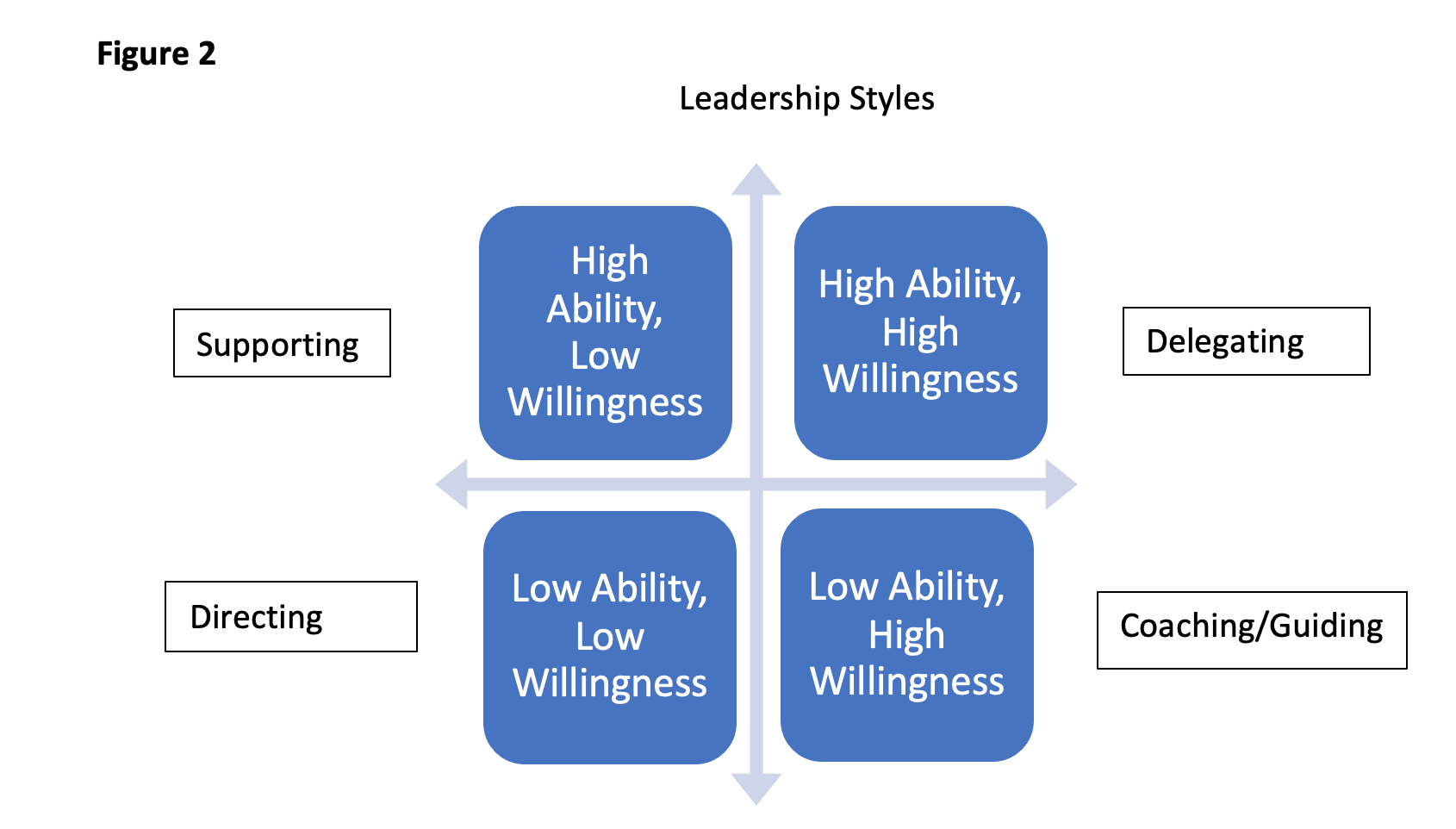

After reviewing the graphic above (Figure 1), assess the readiness level that best describes an individual, your school or organization. Now, review Figure 2 and determine which leadership style you need to move from to the top right corner. Upper right is our goal.

In this post I will provide one strategy that I have implemented over the years. In my book, which is in process, I will provide at least five leadership applications for each quadrant.

Let’s start in the lower left corner of Figure 2 above. These individuals or groups may be new to teaching, a new hire in your company, or just inexperienced in working collaboratively. Yes, they may have book learning and content knowledge. Working toward common goals with colleagues is another level of complexity.

- How do you leverage everyone’s intellectual knowledge base?

- How much did you learn about teaching students in your first year in the classroom?

There is a quote by Joseph Joubert that says, “to teach is to learn twice.” I knew how solve physics and math problems. But, that is not what I was hired to do. I was hired to teach others about physics and math and to solve problems. That is a big difference. Being responsible for thirty moving targets in high school is different than being a student teacher with the master teacher in the back of the room (if you were lucky).

If you are new to a work group, most colleagues and supervisors want to know what you can do. Experience certainly is a plus but not everything. New hires bring new ideas to our work group. New hires, in most cases, do not possess experience with long-term results nor the political savvy to make things happen in a timely manner. The right environment can make that transition much better. It is a collaborative process. How do you bring new people into your organization? What can you learn from new hires? Read Liz Wiseman’s book (2015) Rookie Smarts for some suggestions.

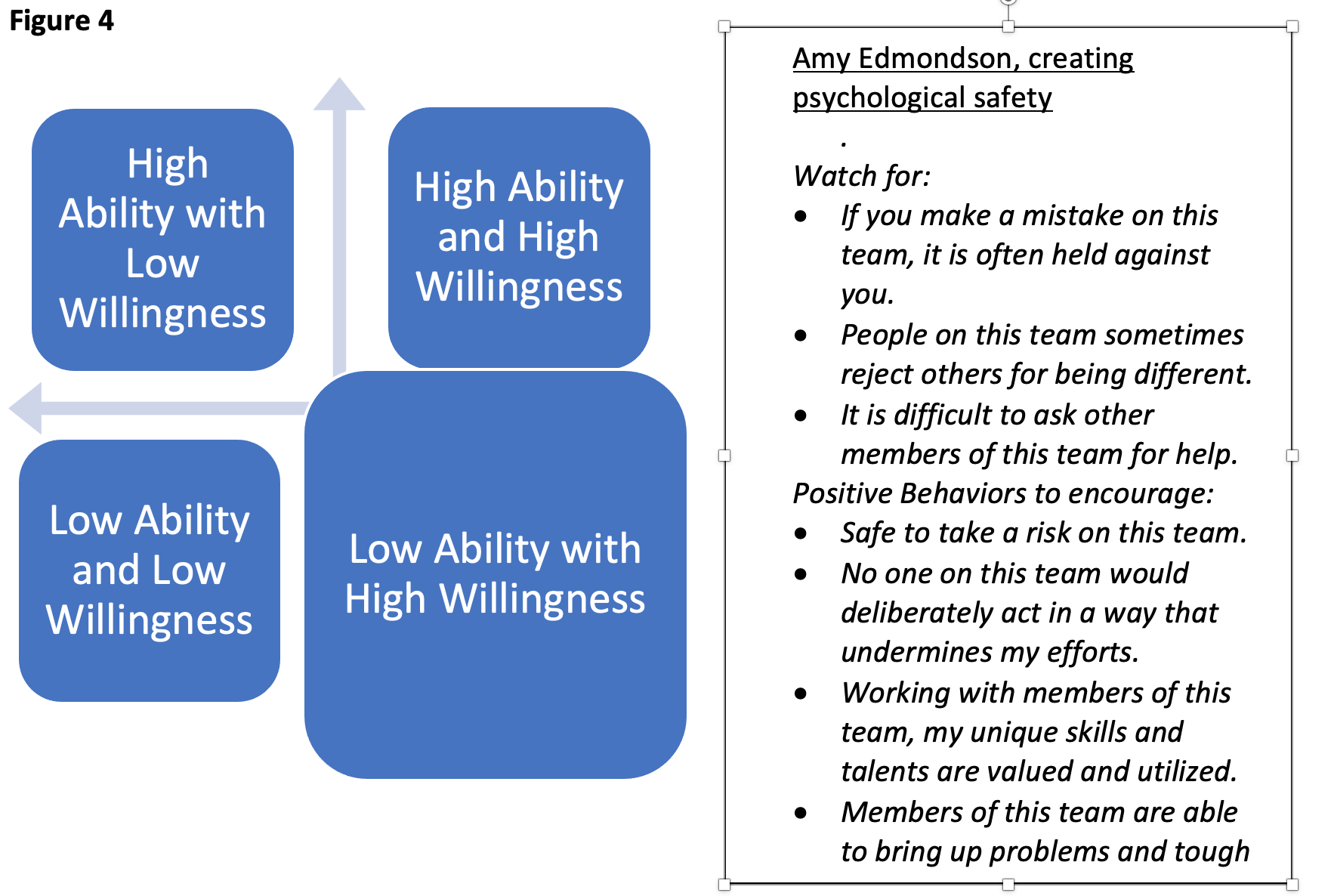

In the lower right column of Figure 3 is low ability and high willingness. The positive about this quadrant is there is energy and desire to learn more. The individual or group is working hard at what they know. They tend to be very social and want to work together. From a leadership style we want to leverage the desire to get better and provide additional instructional repertoire. We want to provide psychological safety to create a climate of learning, not self-protection.

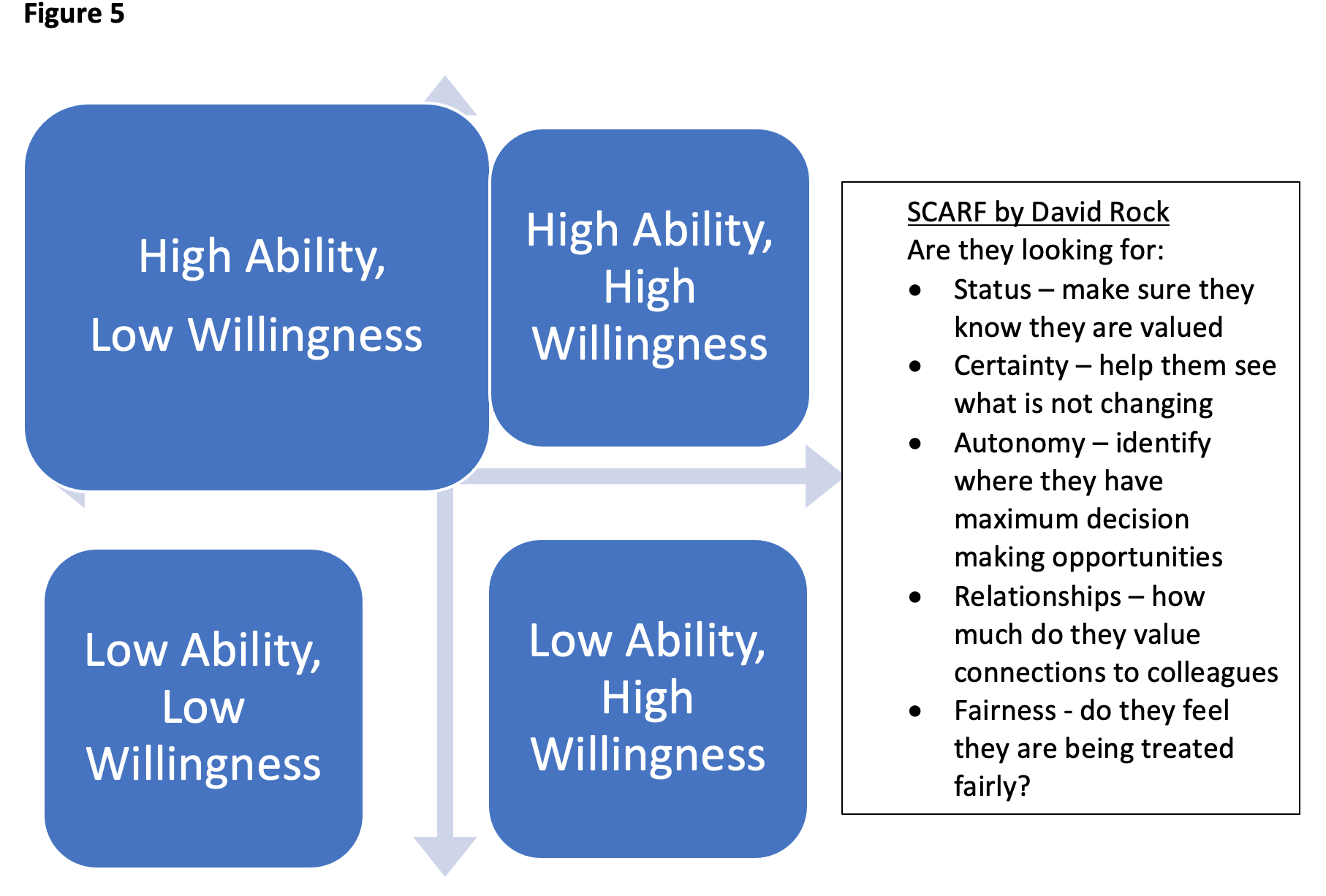

The upper left quadrant of Figure 5 below has been one of the toughest groups for me to deal with as a leader. The individual and/or group are highly qualified, knowledgeable, confident, and know how to teach. The downside is they may want to work alone. A statement that identifies this group for me is, “I am doing a good job. Give me the kids, they will learn, and don’t make me go to meetings.” The problem is they are good and we don’t get to learn from them. It models the Las Vegas motto of ‘what happens here, stays here.’

Using the acronym SCARF to assess what they respond to can help you, as a leader, make connections to them, provide some of what they value, and hopefully bring them into sharing what they know. I call this the Reverse Las Vegas Strategy. ‘What goes on here, leaves here.’ If it is helping students and staff learn, let’s share with everyone.

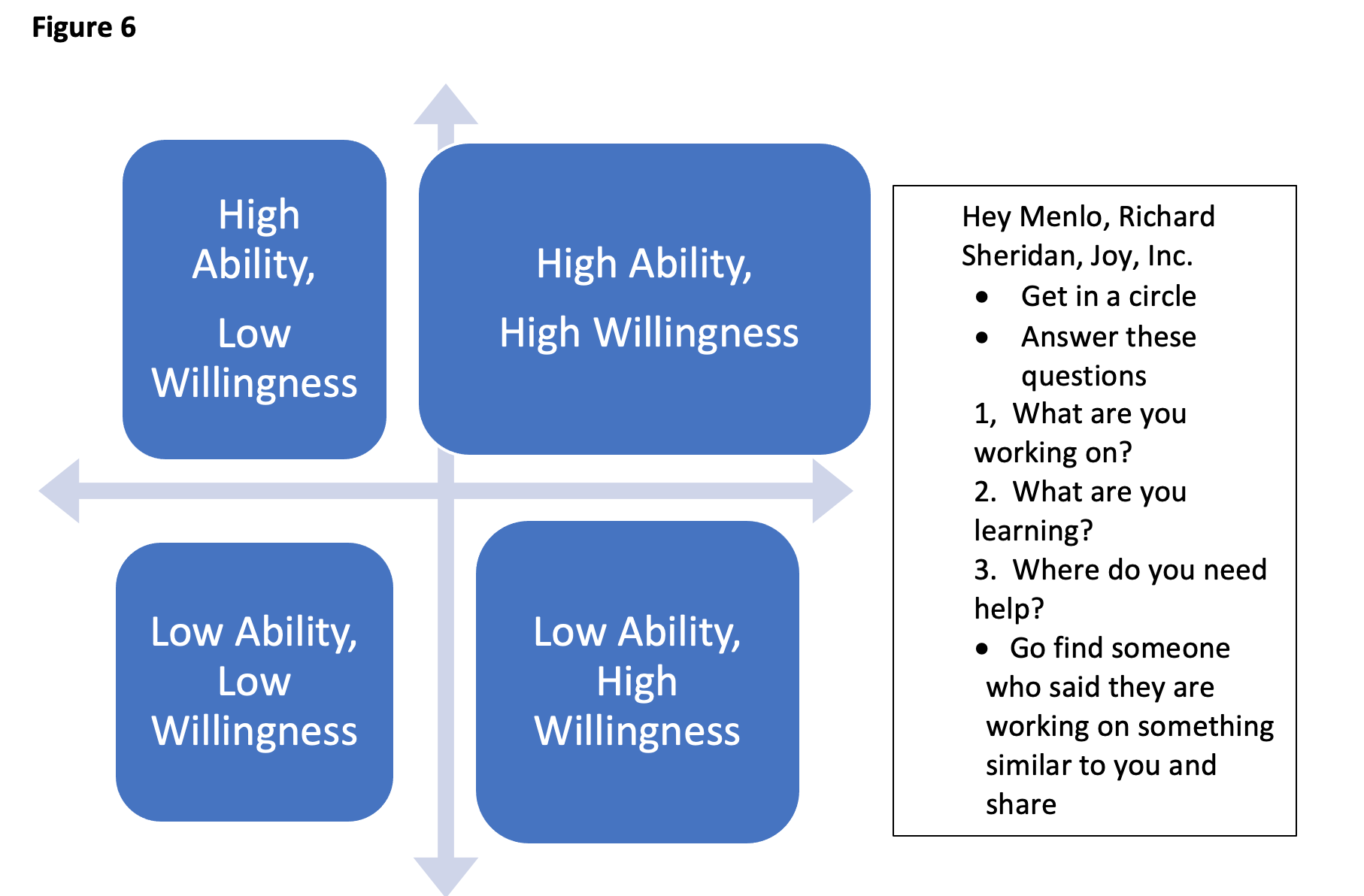

So, the goal is to leverage their knowledge and skills so others can learn from them (Figure 6).

Remember, the goal is getting these highly skilled professionals to share their knowledge, skills, and applications so more of our staff can expand their own repertoire. This group can be great mentors with one caveat. They have to be able to be conscious of the instructional strategies. I have worked with, what I call ‘Magicians.’ You would want your child in their classroom. However, they can’t tell you specifically what they do. They are picking up cues and reacting so seamlessly, they do not recognize the small reactions they make in a nanosecond. I recommend not having them as mentors. I do recommend having them work with kids.

And the final quadrant Figure 6. I call these ‘learning omnivores.’ You can’t feed them enough learning. They are always, yes always, looking for more learning opportunities for themselves, their students, and their colleagues. They can’t wait to tell you about the latest thing they are learning, how they tried it out, and what the results are. For this group, DON’T GET IN THE WAY. Give them as many opportunities to learn and apply as possible. Ask them what they are learning? Let them talk. You will learn a great deal.

I have observed the ‘Hey, Menlo’ process at Menlo Innovations, Ann Arbor, Michigan, many times. Forty-five people go around the room in about twenty minutes. Once they finish, staff finds the person who mentioned something that might help them. The transfer of knowledge is amazing for the short period of time. It is the best PLC I have witnessed. Kudos to Richard Sheridan, CEO, for implementing this. I am grateful that I got to learn from him and Menlo.

OK, Ready, Set, Go. Assess readiness, choose a leadership style, and try it out. If it moves learning ahead, great. If not, try something else. Let’s accelerate our own learning which, in turn, will accelerate the learning of others.

“Give a good idea to a mediocre team, and they will screw it up.

Give a mediocre idea to a great team, and they will either fix it or come up with something better.

If you get the team right, chances are that they’ll get the ideas right.”

Ed Catmull, CEO, PIxar

References

Catmull, Ed (2014). Creativity, Inc.ˆ New York: Random House.

Coyle, Daniel. (2018). The Culture Code. New York: Bantam Books

Drago-Severson, Eleanor. (2016). Tell Me So I Can Hear You. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit. New York: Random House

Edmondson, Amy. (2012). Teaming. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Edmondson, Amy. (2019). The Fearless Organization. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons

Goldsmith, M. (2007). What got you here won’t get you there. New York: Hyperion

Grant, Adam. (2013). Give and Take. New York: Viking

Hargreaves, Andy & O’Connor, Michael. (2018). Collaborative Professionalism.Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press

Hersey, Paul. (2004). The Situational Leader. (4th ed.) Escondido, CA: Center for Leadership Studies, Inc.

Herzberg, F. (2008). One more time: how do you motivate employees? Boston: Harvard

Johnson, Barry. (2020). And: Making a Difference by Leveraging Polarity, Paradox or Dilemma.

Volume One. Sacramento, CA: Polarity Partnerships.

Kim, W.C. & Mauborgne, R. (2017). Blue Ocean Shift. New York: Hachette Books

Lencioni, Patrick. (2016). The Ideal Team Player. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons

Pentland, Alex. (2014). Social Physics. New York: Penguin

Pfeffer, J. & Sutton, R. (2000). The knowing-doing gap: how smart companies turn

knowledge into action. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Rock, David. (2001). SCARF: A Brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others. Sydney, AU: NeuroLeadership Journal

Saphier, Jon. (2017). High Expectations Teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press

Saphier, Jon, Haley-Speca, Mary Ann, & Gower, Robert. (2018). The Skillful Teacher (7th ed). Boston: Research for Better Teaching.

Schein, E. (2009). Helping – how to offer, give, and receive help. San Francisco: Berrett- Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Schein, Edgar. (2013). Humble Inquiry – the gentle art of asking instead of telling.San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Scott, Kim. (2017). Radical Candor. New York: St. Martin’s Press

Sheridan, Richard. (2013). Joy, Inc. New York: Penguin

Sheridan, Richard. (2018). Chief Joy Officer. New York: Portfolio/Penguin

Slap, Stan. (2010). Bury My Heart at Conference Room B. New York: Penguin.

Sommers, William & Zimmerman, Diane. (2018). 9 Professional Conversations to

Change Schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Sommers, William. (2020). Responding to Resistance: 30 Ways to Manage Conflict

In Schools. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree

Sutton, Robert, & Rao, Huggy. (2014). Scaling Up Excellence. New York: Crown Publishing Group

Wiseman, Liz. (2010). Multipliers. New York: HarperCollins.

Wiseman, Liz. (2015). Rookie Smarts: Why Learning Beats Knowing in the New Game of

Work. New York: HarperCollins